Apparently there is a belief held among certain members of the trans community that we should go back in time … back to the days of the DSM III in particular - at least for what is now referred to as Gender Dysphoria. (If you wish to read the DSM III section on Transsexualism, it’s Diagnostic Code 302.50 - in the chapter on Sexual Disorders, I think).

I have opinions.

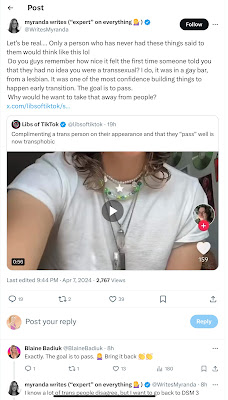

First, let me post the thread that I just read before I go off and explain just how incredibly wrong these people have it.

There are a few things to bring out here. First is a gross misunderstanding of the role / purpose of the DSM and its development. Then we need to get into a discussion of just what treatment for transsexuals looked like back then, because wow - it wasn’t pretty.

The Role and Development of the DSM

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a diagnostic tool. It lays out the criteria which a clinician needs to identify in order to provide a diagnosis of any particular mental disorder that it describes. It is very much rooted in what is often referred to as the “medical model” of mental illness. Many mental health practitioners outside of psychiatry object to this approach for a variety of reasons, including the need for “concrete definitions” of symptoms which often are too narrow to accurately describe the patient in front of them.

First and foremost, the role of the DSM is in providing diagnostic guidelines for practitioners. In other words, it DESCRIBES things and the combinations of features that are usually seen with various phenomena. The DSM does not PRESCRIBE any kind of particular treatment.

The DSM is ultimately a “book of science” - that is to say its contents are a summarization of scientific consensus over many years of development. New versions of the DSM typically come out every decade or so. The DSM III eventually was updated to become the DSM III R (Revised) after a few years of application as practitioners refined its content. Similarly, the DSM IV became the DSM IV TR (Text Revision), and we now have a DSM 5 TR that just came out recently.

Why do new revisions of the DSM come out periodically? Basically it’s because over time studies reveal new things about the various diagnoses in it. We may discover that a diagnosis is entirely incorrect as a separate structure and really belongs as part of another diagnosis entirely (This happened with Asperger’s Syndrome and Autism in the DSM 5). Sometimes scientific study will discover that two previously distinct diagnoses are in fact facets of the same condition (Thus the combination of Hyperactivity Disorder and Attention Deficit Disorder into a singular diagnosis for Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)).

The Evolution of the DSM and Gender Identity Diagnoses

The DSM III prescribes a particularly narrow definition of Transsexualism that talks primarily about those who pursue both social transition and medical (including surgical) transition. That’s a particularly narrow definition, but phenomenologically speaking, it’s not surprising. Up to that point, clinicians like Dr. Harry Benjamin had seen primarily clients who were among the most desperate of cases - those whose distress was so severe that they were desperately seeking any kind of help they could get. In parallel, the notion of sexual orientation was really in its early days as well, and just as Kinsey’s typology for sexual orientations was quite narrow, so was Dr. Benjamin’s proposed typology for gender identity. The result was a predictably narrow definition of transsexuals that ultimately excluded a wide range of people who actually do benefit from the more recent definition used in the DSM 5.

Over the life of the DSM III, practitioners started coming in contact with a wider range of people experiencing gender identity issues. Not all of these people were interested in surgical interventions, some wanted hormone therapy and social transition, but weren’t interested in changing their physical sex. Others started to come forward who had lived lives in great emotional pain because they simply didn’t have the language for what they were experiencing, and came to understanding later in life. Some people previously classified as cross-dressers would come forward and say “you know, I’ve been living as a woman for so many years, and I want to pursue surgery”. In other words, a ton of different paths, and different subgroups of what is now understood to be Transgender started to become visible to the scientific community. Also, children and youth who were experiencing symptoms were starting to be presented at clinic.

The result of all of that was a realization that the DSM III definition of “Transsexual” wasn’t adequately describing the range of people that were being encountered in clinical practice. In the DSM IV, Transsexualism was replaced with the considerably broader diagnosis "Gender Identity Disorder" (GID). As you might expect, GID was broader, and focused much more on the psychological than on the desire to change genitalia as the preceding Transsexualism diagnosis in the DSM III had. In other words, it took a big step away from medical / surgical side of things and focused on matters such as functioning in life. However, over time, even more evidence came to the fore, revealing still more groups of people who experience significant symptoms, but do not fall within the relatively narrow confines of the GID diagnosis. During this period, clinicians started encountering other identities like non-binary, gender fluid, etc., who experienced distress, and were deserving of treatment, even if they fell outside the range of experiences described by GID. Along with criticisms that the GID diagnosis didn't have an "exit criteria" (eg. it was effectively a lifelong diagnosis that persisted beyond treatment), which some transgender people pointed out was damaging to them in their lives because it could inhibit gaining access to some kinds of employment.

The point here is that diagnosis has become broader as the understanding of the range of symptoms and experiences that are involved has changed. As much as this makes some people very uncomfortable, it's good science. Science isn't a "eureka!, I've discovered something", and whatever it may be is cast in stone from that point forward. Especially in the world of mental health and human behaviour, it's a long process of expanding our understandings and making the diagnostic tools more robust and complete.

Winding things back to narrower criteria from the past is fundamentally bad science in the first place.

Treatment Programs

The era of the DSM III was also the same era as hospital-based Gender Clinic programs. As much as the writers of the thread above seem to think it's as simple as "2 years of psychotherapy, 1 year of Real Life Experience, and presto, you can get surgery", the reality of these programs is a whole different thing.

These programs were hugely problematic, with rigid requirements and staging, subjective therapist opinions imposed on clients, and so on. In Canada, we had the program at The Clarke Institute for Psychiatry (now CAMH), and it had more than its share of problems. Controlling behaviours, denying people access to treatment unless they met very arbitrary subjective criteria (appearance - if you weren't already very, very feminine in appearance, you didn't get very far). It was not unusual for these programs to force people to abandon careers and take "more traditionally feminine" jobs, or to insist on living full time for at least a year before you can even access hormone therapy.

Then we come to what happens when practitioners like Paul McHugh get their hands on the programs and the biases they bring to them.

Those programs were straightjackets built on the "medical model" that assumes that the practitioner knows what's best for you. If you didn't fit precisely into the clinical model they had set up, and didn't jump through the hoops in exactly the right order, you got kicked to the curb.

Today, we don't have rigid programs for a reason: They DON'T WORK. They ultimately harm people. While I understand the motivation to "ensure that nobody who doesn't need to transition actually does", I think it's also misguided. With "regret" rates trending around 1%, it's well below the rates for most major medical procedures. Knee replacements have a regret rate around 20%.

The reason that therapy is not a mandatory part of gender transition is because not all people actually need it. In general, therapy has more to do with developing resiliency skills, and learning to cope with some of the slings and arrows that are often lobbed at transgender people. Making it "mandatory" seems unnecessary, and will do little for clients who feel that they are attending "because they must" (in fact "mandated" therapy is known to be generally ineffective).

So, anyone who thinks that those programs of the past were ever "good" doesn't understand the poor assumptions, and horrendous practices that were part of that era. The only thing I will consider a "good" coming out of them is the fact that they added to an ever increasing body of data that ultimately showed them to be unnecessary.

Gender Dysphoria and Validity

I want to point a couple of additional things out here. There is no 'right way' to experience your gender identity. There is absolutely no 'right way' to be transgender. If someone comes along and starts talking about rolling things back to the past, it's because the realities that proper scientific study has revealed make them uncomfortable. That is on them. Your gender, your identity, is valid, and nobody has a right to take that away from you just to make their own lives a little easier.

No comments:

Post a Comment